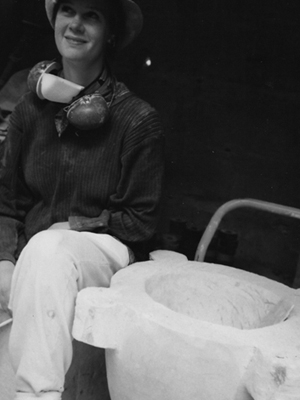

Coming from a theater family, my own sculptor’s career started in the early nineties. Some months volunteering at a stonecutter’s workshop near Munich, followed by a 9-year work and study stay in Italy – several year’s apprenticeship in classical marble sculpting studio Ricci, Pietrasanta, free artist’s studio Leonardi in Querceta (now studio Pescarella), then Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara completed by the

diploma in sculpture in 2001.

Additionally enriching and formative were a great many of international work and study travels.

Since 1999, I have been living and working as a free sculptor and art tutor near Munich, Germany and exhibiting internationally. The way I work is classical modelling and sculpting – during my formation, I was strongly influenced by the art of great ancient and contemporary sculptors as well as by classical sculpting techniques.

That is why my I work is made by hand and characterized by these little, hardly perceivable imperfections and asymmetries which bring a bold surface or a sharp line to life. I am using any modelling material such as clay, plaster or wax on my way to the final material – mainly bronze, but also marble or glass.

My sculpture’s design language is the result of an intensive observation of nature amongst others – a significant inspiration since my childhood has been the ocean and its soul. It is all about tension, suspense and release in any moment, be it visible in movement or invisible in stillness.

Harmony is created seeking out a way out of suspense – my sculptures show one moment in this eternal continuous procedure.

BINDING UNLEASHED FORCES

ON THE SCULPTURAL WORK OF KATHARINA FREITAG

(Author: Lena Rupprecht, mundus issue 2/2009)

“Disgust arises from all satisfaction, because it is precisely in the tension of forces alone that lust lies,” wrote the 19th century playwright Christian Friedrich Hebbel. Few sentences give such a precise answer to the question of what the criteria for good art are. Tensionless satisfaction very soon bores.

However, artists who know how to keep two opposites in mutual tension in their work create something timelessly valid: an image of the polarity of human existence. Man should live as if he had eternal life and at the same time behave as if he had to die tomorrow.

Then great things are created.

The same applies to a work of art. If the artist succeeds in making explosive forces visible in their work and simultaneously containing them through a strict form that, however, always seems threatened by an inner explosive force, then they create not just art, but great art. Those who suppress forces destroy the tension just as much as those who unleash them. Containing forces, on the other hand, creates that fascinating tension in the radiance of an artistic work that gives a painting or sculpture an irresistible aura for centuries. The Munich sculptor Katharina Freitag masters this rare art: a sorceress – in the truest sense of Goethe – who knows how to control the spirits she summons. This is visible. In every sculpture. From the Forge of Hephaestus Katharina Freitag’s sculptural work has a history. It has its roots in a family of artists. Her parents ran a theater, her grandfather was an opera singer. Katharina Freitag initially attempted a middle-class existence, studying commerce, followed by French, German, English, and Spanish literature, but found no real satisfaction in these subjects. When she saw the film Camille Claudel starring Isabelle Adjani in 1989, she realized that sculpture was her calling. This was followed by an internship with stone sculptor Helmut Schlegel in Oberhaching near Munich, advanced training with sculptor Annette Rowdon and painter Elisabeth Lyons in London, and several years of study with Italian sculptor Alessandro Ricci in Pietrasanta. Katharina Freitag received her systematic training in sculpture at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara and a one-year nude study at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Geneva. From 1991 until her move to Munich in 1999, she lived and worked in Italy, acquiring sculptural knowledge in Tuscan workshops, a skill passed down from masters to students since the Renaissance. Imagine: a summer day in Tuscany. A casting is underway, the skilled caster pours the molten bronze into a prepared mold, followed by a celebration with wine, bread, and olives. These are moments full of archaic power. They shape an artist for a lifetime. Alessandro Ricci, the stone sculptor, taught her a sense of marble: “You must treat it like your lover. If you are rough with it today, it will pay you back tomorrow.” From Ricci, she learned to distinguish between the soft and hard sides of a block of marble, to perceive it as something natural and alive. She also learned to hear and interpret the different sounds the stone makes—depending on where you tap it. This gave her an instinctive feel for marble, travertine, alabaster, and sandstone, for their textures and their inherent possibilities. Katharina Freitag works in stone and bronze. What fascinates her about bronze is the archaic quality of the material.

People have been working with this metal for more than 5,000 years. The name is derived from Brundisium, the Latin name of the southern Italian city of Brindisi, a stronghold of bronze processing and trading in ancient times. It is not without reason that the material used for bells and cannons continues to fascinate artists and viewers alike. Casting hot bronze is a creative process, like working with molten magma. It gives the artist the feeling of recreating the earth once again. People heard the sound of bronze when it rang during Holy Mass and when cannons thundered in war. In a mysterious way, this metal in particular has an intrinsic connection to the theme of harmony. The history of this term reveals this: Harmony is derived from the ancient Greek word harmonia, meaning the joining or connection of two opposite poles. Harmony, seen in this way, is not a state free of conflict and tension, but rather a state created by the binding of two opposing forces. In Greek mythology, the goddess Harmonia is the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, the god of war and the goddess of love. Aphrodite was originally married to the blacksmith god Hephaestus, but desired Ares, the god of war, much more than her rightful husband. Her union with Ares produced five children, among them Eros and Harmonia. True harmony is never flat. It is full of tension, for it arises from the union of the irreconcilable, a child of love and war. An ancient story – always new. Duality, polarity, and the interaction of bonding and disintegration: these are the leitmotifs in all of Katharina Freitag’s works. She conceives many sculptures as two-part sculptures from the outset, for example, “You and I.” The appeal of these two-part sculptures: when placed in different positions relative to one another, they tell a new story each time. The opposite direction of Danza nell’universo or Bianco – Nero is similar. Some works take on a hybrid position. Thus, two spirals can be positioned side by side, with their upper ends facing outwards or inwards, with both points to the right or both to the left, lying down or standing upright. They can also be placed individually. Taken on its own, the spiral expresses polarity by restraining the springing force of its arc, preventing it from springing up with the hardness of its material. Katharina Freitag’s sculptures are static, but they don’t stand still. They don’t rest. They tell a story that is already continuing at the moment of observation. They come from somewhere and go somewhere else. They act as a catalyst for the viewer, inspiring them, triggering their own developments. There is an enormous flow within them, despite their hardness and rigidity. The ideas underlying them arise in the unconscious and are therefore pure, that is, unadulterated, existential, primal human. They tell the story of connection in separation and of encountering oneself in the other. To be able to create in this way, one must have trained one’s eye for a long time. Katharina Freitag has done so: on Michelangelo, of course, but also on many other old and new masters such as Donatello, Cellini, Ghiberti, del Verrocchio, Bernini, Claudel, Rodin, Maillol, Giacometti, Brancusi, Marini, Mitoraj, and Alexander Calder. Those who would like to see more of the artist’s works can view them in the showroom of the Munich Art Foundry or visit Katharina Freitag in her Grünwald studio. In summer 2009, the artist will be represented at the Sonnenwald Sculpture Garden with the sculpture “Attraction.”

It’s well worth a visit.